|

Every mention of Pettah stirs a flutter of emotion. It has always been a ride in my mind: the labyrinthine streets, the cacophony of voices, the mishmash of scents, and the unspoken rules of survival. |

|

|

For me, Pettah is a tapestry of contradictions: a place where the past and present collide, and chaos hums with life. Firstly, Pettah is a maze; an intricate web of streets and cross-streets, each brimming with purpose, yet enigmatic to the uninitiated. Navigating it feels akin to deciphering a map without a legend. Asking for directions is an option, of course, but therein lies my second deterrent. Pettah, to me, carries an undertone of unease. The cacophony of women haggling, indifferent to whom they address or how, is unsettling. Chamara, or “Chamara Ayya,” as I affectionately call him, is a boomer and a friend I made at work by not calling him uncle.

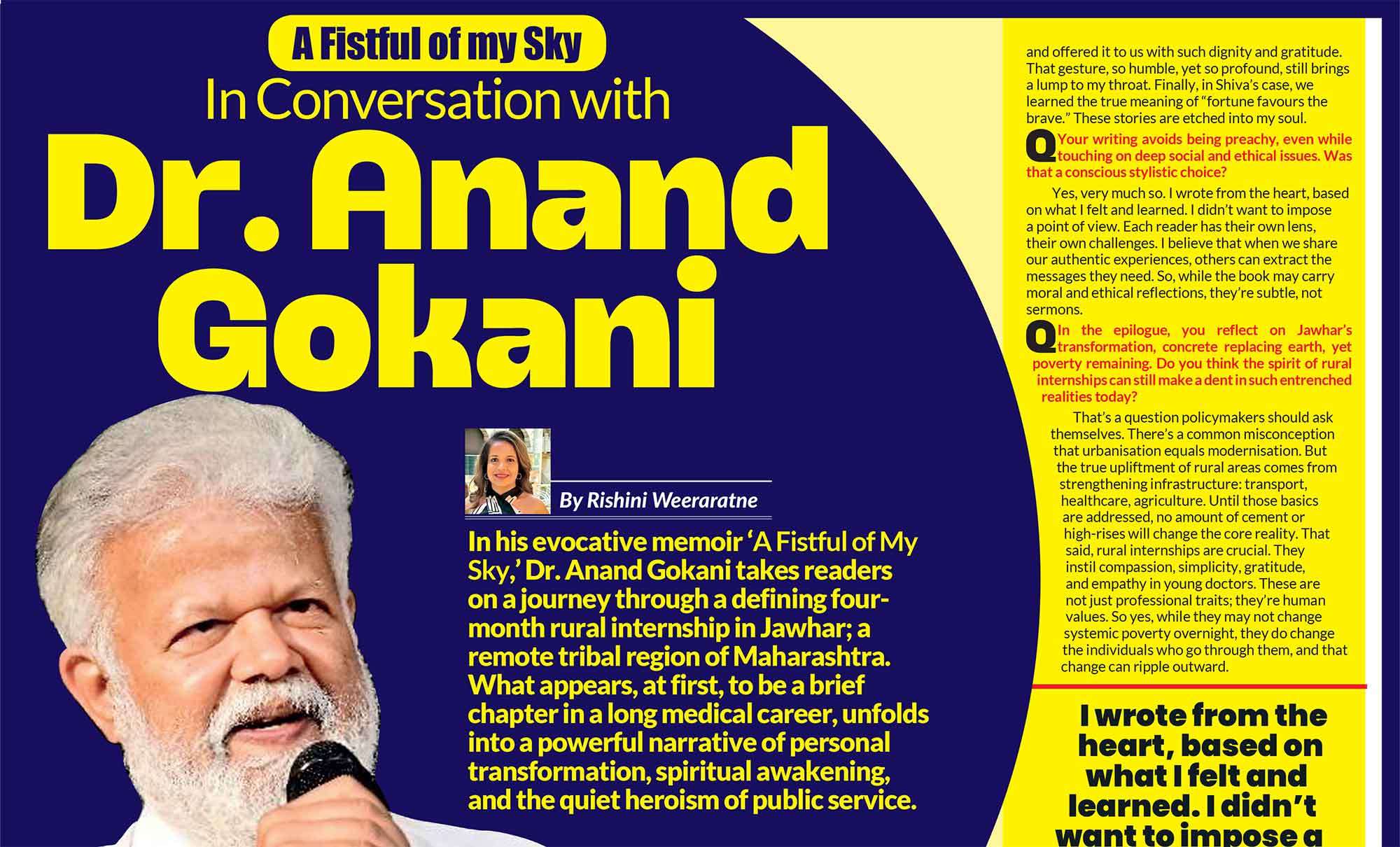

His voice carries the weight of someone who has seen Sri Lanka through its maze of transitions. “Pettah isn’t just a market,” he said with a glint in his eye, “it’s a documentary where every corner holds a piece.” So, armed with curiosity and a van full of friends I made at work; Pathum, our photographer; Gayantha, our ever-eager conversationalist; and myself, a writer who likes to think she is good at what she does, with an open notebook, we set off.

We disembarked near the “Pittu Bambuwa,” now the BOC head office. The towering cylindrical edifice, colloquially dubbed the “Pittu Bambuwa,” is an emblem of this storied past. Once a marvel of concrete ingenuity in 1987, now home to the Bank of Ceylon, it stands as a silent witness to the city’s evolution. Its shadow looms over a populace that oscillates between pride and lament—pride for the heights the city has scaled, and lament for the tragedy that lingers in its wake. None more poignant than the Central Bank bombing of February 1996. The suicide attack, orchestrated with chilling precision, extinguished 91 lives, and left over 1,400 injured.

The echoes of that fateful day reverberated from Fort to Ratmalana. Chamara’s face tightened with emotion as he pointed out its historical significance. From there, we wandered to a curious relic: the prison cell of King Sri Wickrama Rajasingha. Painted pale yellow and crowned with fish-scale motifs, it stood as an ambiguous monument. The structure also includes a statue of King Sri Wickrama Rajasingha, displayed in a cavity on its rear wall, commemorating the king’s supposed imprisonment here after his capture by the British in 1815. Historical records provide a different narrative. The Government Gazette (No. 704, dated March 15, 1815) states, “On the Monday following, Major Hook, with the detachment under his command, escorting the late King of Kandy and his family, entered the Fort. He is lodged in a house in the Fort which has been suitably prepared for his reception and is stockaded round to prevent any intrusion on his privacy.”

Similarly, Dr. Henry Marshall’s writings in Ceylon: A General Description of the Island and Its Inhabitants (1846) reinforce this account. According to Marshall, the king’s residence was spacious and well-furnished. Upon his arrival, King Sri Wickrama Rajasingha reportedly remarked, “As I am no longer permitted to be a king, I am thankful for the kindness and attention which have been shown to me.” If the king’s house arrest in a fortified residence is well-documented, then what is the true story of this monument? Chamara’s commentary brought the space alive, questioning the veracity of its history. Was it truly a prison cell, or merely a sentry box? “Does it matter?” he asked. “What matters is what we’ve chosen to remember and what we’ve allowed to fade.” Our eyes instinctively searched for closure, landing on the clock tower that marks the zero-mileage point in Colombo. In 1914, the original clock was replaced with the one we see today.

Interestingly, the original mechanism was crafted by the renowned watchmaker who also created the iconic Big Ben in London. Whether this tale holds true or not is Chamara’s claim—I’ll let him take the fall if it proves false, though I did verify what I could. This made me reflect on how much we tend to overlook in our daily lives. We’re so eager to become tourists on long weekends, rushing to distant destinations to marvel at history and beauty. But oh, isn’t the beauty right here? Don’t we already possess treasures of immense value, just waiting to be rediscovered?

A Bombai Muttai uncle crossed the road right with us, strings of spun sugar stretched into light, sticky strands, like a local candy floss but thicker and more satisfying. Seemingly indifferent to us, he knew the game well. His candy, irresistible and nostalgic, could awaken the inner child in anyone, so he wouldn’t have to worry about the adult addicts. Without a glance our way, he directed his attention toward a child, hoping to tug at the mother’s heartstrings. As we neared the Pettah market, having some sticky candy floss, the noise escalated, embodying the city’s lively chaos. The bustling atmosphere was punctuated by rows of Sri Lankan ornament sellers. Pathum’s attempt to photograph them stirred an argument. It was clear—the people were wary of the media’s power, knowing it could bring about change for better or worse. Yet their reaction, though understandable, was neither cutesy nor demure, snuffing out our enthusiasm all the same. We started our journey on Malwatta Road, a surprising escape from Pettah’s usual chaos, it’s neat, fancy bricks lending a brief moment of calm. That serenity, however, was quickly broken by bus 107 aggressively charging towards us, reminiscent of a white van

from 2017.

Malwatta Road is a treasure trove for those seeking shoes, bags, and watches. I even spotted trendy baguette bags in a small shop, a nod to modern fashion amidst the hustle. We stopped by Kevin’s shop, Rainbow Bags and Luggage, which faces the main street. Kevin, ever the optimist, shared how business has been struggling due to fierce competition across the road and seasonal downturns. Yet, he managed a thumbs-up and a smile, promising a 10% discount if you mention The Sun. As Pathum grabbed a paper bag of cassava chips, we moved forward, our curiosity leading us to The Nanayakkara Shoe Palace.

Here, we met Sudara, the owner, who now carries forward the business once led by his late father. A remarkable individual, Sudara holds a Bachelor of Science with honours in biochemistry and an MBA in Hospital and Health Services Management. He skilfully balances his aspirations for the future with a deep commitment to preserving his father’s legacy. The shop caters to all kinds of customers, offering a discount of 10-15% for The Sun readers. Chamara, our guide and the unofficial mayor of Pettah, seemed to know everyone, embodying the spirit of human connection that defines this vibrant marketplace. While the shop owners weren’t particularly interested in media, they welcomed Chamara’s chat with the warmth of an old friend. As we moved on without Chamara, his trusty Nokia button phone (with a Samsung smartphone as a “sidekick”) ensuring he was just one ringtone away.

Next, we headed to Maliban Street, a hub for watches, wedding stationery, party supplies, and cake boxes. Chamara joined again and joked that this was the perfect spot for Pathum and Gayantha—one who’s forgotten his email password and the other is yet to install a dating app. My attention was quickly drawn to a fruit cart manned by Nihaz, who sold mangoes and guavas sprinkled with seasoning. He has been at this for nearly 40 years, proudly calling it his “free and independent” trade. Nearby, Officer Jayakody, stationed at the Pettah Police Station, was on duty with a fellow officer on a motorbike. We stopped for a quick chat, and Officer Jayakody shared his two-year experience in Pettah.

Despite Pettah’s reputation as a chaotic marketplace, he hasn’t encountered any unusual complaints about safety. However, he acknowledged concerns about women’s safety and minor thefts, often linked to substance abuse.

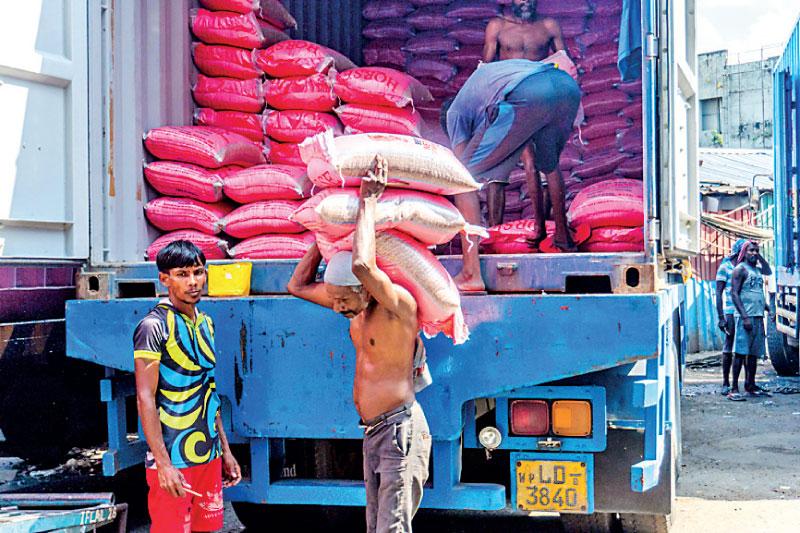

Amid the crowd’s restless tide, the nattamis navigate with precision, halting their carts with unflinching resolve. They bear the weight of unimaginable loads on their weary spines, yet in a single, decisive moment, they pause—to spare even the faintest graze of another. Turning towards 2nd Cross Street, Chamara introduced us to Fazmeer, a trader selling undergarments and textiles imported from China. For 33 years, he has continued his father’s business, earning a stable income he proudly calls “independent.” “Alhamdulillah,” he said with a smile, expressing gratitude in Arabic for his livelihood. When asked if he faced challenges in his trade, he explained that his honesty in business kept conflicts at bay. Pointing to the Bo tree at the end of the road, he remarked that it serves as a silent witness, deterring wrongdoing. Curious, I asked how a Muslim man places faith in a Bo tree. Fazmeer’s response was heart-warming: “Sri Lankans have faith in it, so I do too.” While speaking, his eyes kept darting across the crowd, searching for someone. Eventually, he revealed he had found a wallet on the ground and was holding onto it until its owner returned.

Amidst the sea of shops, we walked ourselves into the 1st Cross Street, where you could find backpacks, watches, postal stationery, art stationery, and some electronic shops here and there too. One particularly crowded store caught my attention: Trans Asia Cellular (Pvt) Ltd. Inside, the buzz of customers swarmed around electronics and phone accessories. Gayantha, who kindly guided me through the store, explained that the shop’s low wholesale and retail prices draw massive crowds. I purchased two tempered glasses for my phones, impressed by the efficiency and affordability. Further along, I met Aaqib, who has been running his father Mufeel’s business for 25 years. He shared that Pettah is a place where racism and discrimination hold no ground. “Even during Sri Lanka’s toughest times, people here supported one another,” he said. Pettah, according to Aaqib, is the embodiment of unity. His business, which imports phone accessories, spans three branches: Kurunegala, Pettah, and even the UAE. The global reach of his enterprise was inspiring, proving that Pettah is not just a local marketplace but also a window into Sri Lanka’s interconnectedness with the world.

To recharge, we decided to stop by a Bombay sweet shop on the main street for the iconic Pettah falooda. Chamara, ever the quintessential Sri Lankan, opted for an avocado juice instead, while Pathum, Gayantha, and I indulged in the falooda—one of the main reasons for our trip to Pettah. Exiting the sweet shop, we were greeted by a man shouting, “Hundred for a dollar! Hundred for a dollar!” While the boys brushed it off as another quirky Pettah vendor, I paused, intrigued.

The man, holding an aluminium dollar note, explained he’d been selling this novelty for over 30 years. He admitted that while his income ranged from 2,000 to 3,000 LKR a day, he felt uncertain about the future of his small business. Yet, owning it gave him peace of mind. Following Gayantha’s lead, we ventured toward a fragrant lane, home to a bustling perfume bazaar run by a young entrepreneur who exports all sorts of perfumes and hopes to expand into the One Galle Face Mall soon. As an added incentive, he mentioned offering a 500 LKR discount on the total bill if customers mention The Sun.

Moving further, the 3rd Cross Street revealed its treasures: traditional Indian sarees, lehengas, and shalwars for special occasions, along with mechanical equipment, weighing scales, and cake tools. On the 4th Cross Street, wholesale grains, fresh produce, dry rations, and spices were the highlights.

Bungasal Road showcased artificial flowers, home décor, and garden decorations, while Perera Road brimmed with fermented seafood like dry fish and Maldive fish. I couldn’t speak to anyone here because they were dealing with customers, as they were mostly groceries and fast-moving goods, and I didn’t want to interfere with their business. Each street offered a distinct identity, from the electronics and cosmetics of Kumara Road to the glassware and ornaments on China Street.

Gabo Road added a mix of Ayurvedic and Western medicines alongside baking equipment, while Olcott Mawatha and Hetti Weediya offered fresh produce and gold jewellery, respectively. Pettah, in its entirety, felt like a world within a world, where sellers and buyers

shared a symbiotic relationship of gratitude and mutual respect. As exhaustion crept in, I joked with Pathum and Gayantha about Chamara. “If he gets unfit from all this walking, we might have to send him back to work or let him rest at a restaurant,” I teased. Yet, by the end of it all, it was me leaning on Chamara for support, utterly drained. His energy and endurance had

outlasted us all. Arm in arm, we made our way back to the landmark we had agreed upon—the majestic red mosque—waiting for our transport to arrive. As we waited, we encountered an individual who caught my attention. His demeanour exuded responsibility, but his expression carried a sense of disappointment— like a manager expecting better from an employee but receiving nothing at all. Intrigued, I approached him. He seemed startled at first but quickly composed himself, as if he knew it was his moment to share his story.

Mr. Jayakody, as he introduced himself, is a cleaner employed by a company contracted to maintain Pettah's cleanliness. He took a deep breath before speaking, his words heavy with exhaustion. Two of his colleagues had been hospitalized recently, and he himself was battling a fever, currently undergoing treatment. Despite his condition, he wore a mask diligently. He revealed a harsh reality that left me shaken. The shopkeepers in the area often let their trash pile up until it spoiled, forcing cleaners like him to sift through decomposing waste. He showed me his bare hands, emphasizing the lack of protective equipment as he sorted through rubbish crawling with worms. “If we don’t come to work, we can’t eat. If we come to work, they make us lose our appetite to eat," he said. "If we don’t swim through this dirt, which could easily be managed with daily disposal, we won’t survive.” Yet, despite the appalling conditions, he admitted he liked his job. He wasn’t doing it for the media, the government, or accolades. His passion for keeping Sri Lanka clean was genuine. He treated Pettah like his home, even as those around him neglected their responsibility and allowed the trash to rot before handing it over to him.

The irony of campaigns advocating for a "Clean Sri Lanka" felt stark. Was the nation still caught in a loop of superficial efforts, I wondered? While I was absorbing his story, people around us began demanding that he clean up nearby trash. Their disregard infuriated me. I stepped in and said, “I’m sorry, but can you give us a few minutes?” Turning back to Mr. Jayakody, I asked for his contact number, promising to follow up. As the day waned, exhaustion set in. We found ourselves leaning on each other until the van came to pick us up. Chamara instead said, “This,” he said, gesturing to the bustling street outside, “is the real Sri Lanka. Not the polished tourist spots, but this—the grit, the grind, and the grace.” Pettah had drained us physically but filled us emotionally. It reminded me that beauty lies not in perfection but in authenticity. As we leaned on each other, navigating the final stretch back to the van, I realized that Pettah wasn’t just a market. It was a microcosm of Sri Lanka itself: messy, resilient, and undeniably alive.

Thaliba and Chamara

The bustling atmosphere was punctuated by rows of Sri Lankan ornament sellers.

The bustling atmosphere was punctuated by rows of Sri Lankan ornament sellers.